A Return to 'Happy Mistakes'

How 3D printing can influence

the architectural design process

Issue 309, February 2020, P. 102-103

Architecture Ireland Article - link

Many architects will have a complicated relationship with making models. Fond memories of simpler times quickly give way to what were actually coffee-fuelled, red-eyed, all-night marathons where fingers could be both glued together and covered in scalpel cuts in equal measure.

However, the relationship between the act of physically making and the design process formed a key part of our education in helping us to understand space and scale. Dr Simona Valeriani, who is leading an international research network on ‘Architectural Models in context: creativity, skill and spectacle’, highlights the critical relevance of models to the design process as ‘tools for thought and communication’. She says that they help us ‘to make invisible design processes visible’ and to document ‘moments of communication that are otherwise ephemeral’. According to Dr Valeriani, unlike any other media, models ‘directly convey the embodied 3D qualities of a building and have, since the Renaissance, been seen as the most comprehensible form of architectural representation’.

However, this pivotal role in the design process hasn’t prevented many of us laying down our scalpels and repurposing our cutting mats as mouse pads in recent years. This has been less a defiant downing of tools but rather a laying down of arms – a surrender representative of the wider shift from physical, hands-on skills to digital competencies. Emerging graduates and young architects are no longer tasked with making concept and competition models. Their literacy in quick and accurate computer modelling, along with creating effective visuals, allows for the leapfrogging of a traditional pillar of the architectural design process.

“What we lose from this digital allegiance are the venerated ‘happy mistakes’ that might arise in exploring a design through model making.”

This shift in skillsets is only one of a range of contributing factors that explains an increasing emphasis on visuals rather than physical models. The comparative ease of delivering CGIs and animations, along with the fact that visual images can be more justifiably charged to clients (both because of their efficiency and defined value) creates a case for residing within a digital bubble. Furthermore, visuals require little explanation. Whereas models allow viewers to read between the lines, visuals immediately speak the client’s language. It’s clear the choice comes down to ease and simplicity; presenting visuals to communicate design is more in tune with current workflows. What we lose from this digital allegiance are the venerated ‘happy mistakes’ that might arise in exploring a design through model making.

Such a move from manual/2D workflows to digital/3D methods does not mean that we need to sacrifice architectural models entirely though. 3D printing technologies allow us to take advantage of these new workflows in producing quick, affordable, and highly detailed representations of our digital designs. Critically, we can now make 3D models directly from 3D design data, as opposed to traditional model-making methods which require a return to 2D drawings to then produce a 3D model.

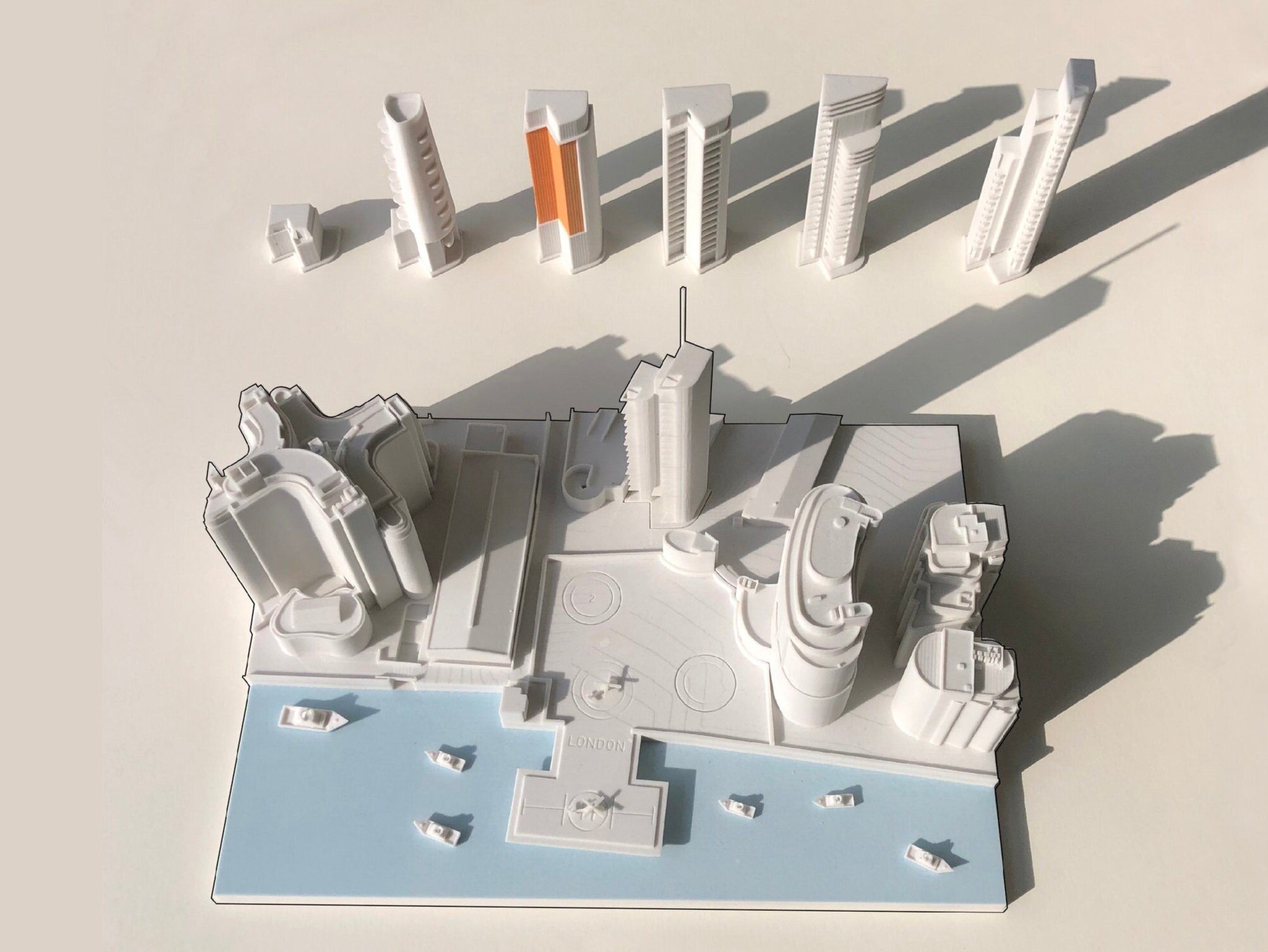

Prototyping through 3D printed models for Corstorphine + Wright Architects

3D printing is probably better known in its role as a prototyping tool, rather than as an approach to architectural model making. However, model making is undeniably a prototyping exercise, we’re just used to softer terminology for it. If we can begin to alter our perception of 3D printing in the architectural domain to begin to actively experiment with this new medium, both as a presentation method but more importantly, as an iterative design tool, it could present new ways to think about structure, form, and the construction process. We can begin to expose new ‘happy mistakes’.

In direct comparison with traditional model making methods, 3D printing technologies offer a range of new materials with varying qualities: transparent v. opaque, flexible v. rigid, smooth v. coarse and layered, full colour v. monochrome. Much like traditional model making, the choice of one or a combination of many helps to reflect the desired design; with the aid of technology though, many more options and varieties can be tried and tested prior to making a final design decision.

3D Printed Organic Forms in various finishes.

3D printing has the advantage of creating organic shapes and delicate structures with ease. However, it also has its own constraints, which are individual to each technology. Each constraint will influence your model design choices and consequently the overall design, whether that be the size of the printing bed, the strength of the material, detail achievable, appearance, or the post-processing methodologies.

On a practical level, for example, only being able to 3D print a facade element at an oversized thickness might affect your resulting detail, while the monolithic aesthetic of some materials and processes might lead you down the path of more massive structures. On the more theoretical side, the ability to easily create elaborate, complex, organic physical forms has the potential to test and experiment with solutions that would previously have been difficult to make or even imagine.

To illustrate the influence of 3D printing on how architects might think and make, some examples which actively utilise these processes are discussed below. Critically, cases involve both the prototype scale and 1:1 built forms.

Make Architects, headquartered in London are – somewhat evidently from their name – focused on design through making. While they are encouraged to work with their hands, they have also invested in a bank of twelve Ultimaker ‘desktop’ 3D printers which allow for continuous 24/7 design development. It’s an approach that saw them shortlisted in the Best Use of Technology category in the AJ100 Awards (You may recognise the 2019 version of these awards)

We set up Fixie, the architectural 3D printing specialist with a similar aim to help build up a greater knowledge base of 3D printing within the architectural ecosystem. By making ourselves available as the ‘architect's 3D printing assistant', we hope to inform architects of the benefits and constraints of this technology. We know that architects are thinly spread and 3D printing can be a daunting additional task to approach; our aim is to make complex digital designs 3D printable. This involves a process called ‘file fixing’, where model files are edited to ensure that they print in the specified technology, with the desired detail, and that they survive any post-processing and finishing tasks. Architect's files need this special treatment as they're predominantly works-in-progress, not the finished articles that 3D printers normally encounter.

Until now, this article has discussed 3D printing solely with respect to the production of replicas and scaled working models. However, there are already numerous organisations who are thinking bigger; thinking about how 3D printing can offer an alternative to current methods of construction – allowing for decentralised, disaggregated, and more sustainable production methods.

AI Build emerged out of Zaha Hadid Architects. They have developed large-format robotic 3D printers that can create intricate parametrically modelled forms (akin to Zaha Hadid’s designs). These printers can create usable furniture and sculptures modelled in such a way that the structure is self supporting. Because of this integral strength, multiple parts can also be pieced together to create elaborate, expansive forms – 3D printing being a potential catalyst for more organic and efficient structures.

DUS Architects, based in the Netherlands, have also created their own 3D printer – XL 3D Printer – in collaboration with Ultimaker. They’re using this 3D printer to create 1:1 building elements, including facade details, benches, and even a micro-home. Using 3D-printed elements, in combination with traditional building materials, they’re creating practical design solutions.

Aectual has emerged from DUS to pursue this avenue of thinking; they’ve turned the approach on its head by, among other things, using 3D printing to create formwork for more experimental concrete structures. Here, 3D printing is offering a way to reinvent existing materials.

XL 3D Printer used by Aectual to 3D print the floor of Schipol airport

However, you don’t have to be changing an entire industry with your explorations into 3D printing; architects can benefit through quietly and quickly exploring facade detail options or massing proposals without the fear of scalpel blades. Although it is an engineered response to a traditional task, 3D printing is open to exploration, to pushing rules and boundaries, and to leading you on an unexpected journey.