Maynooth University Students’ Union Building - Scott Tallon Walker Architects

It might be safe to say that architectural models are less of a mainstay of architects’ offices than they formerly were. These days, you’re more likely to trip over an electric scooter than a design model.

That might come across as a strange thing to say coming from a model-making business, but when CGIs, animations, immersive experiences are now both possible inhouse (albeit to varying standards) and comparatively more affordable then it was almost inevitable that this would happen in a world that often focuses on efficiency over process.

It’s also likely safe to say that 3D printing of architectural models has been an area dabbled in by many and for many of those; never dabbled in again. Deterred by poor experiences, poor results and high costs; 3D printing has also been relegated in some departments to ‘’not quite good enough/not quite there yet”.

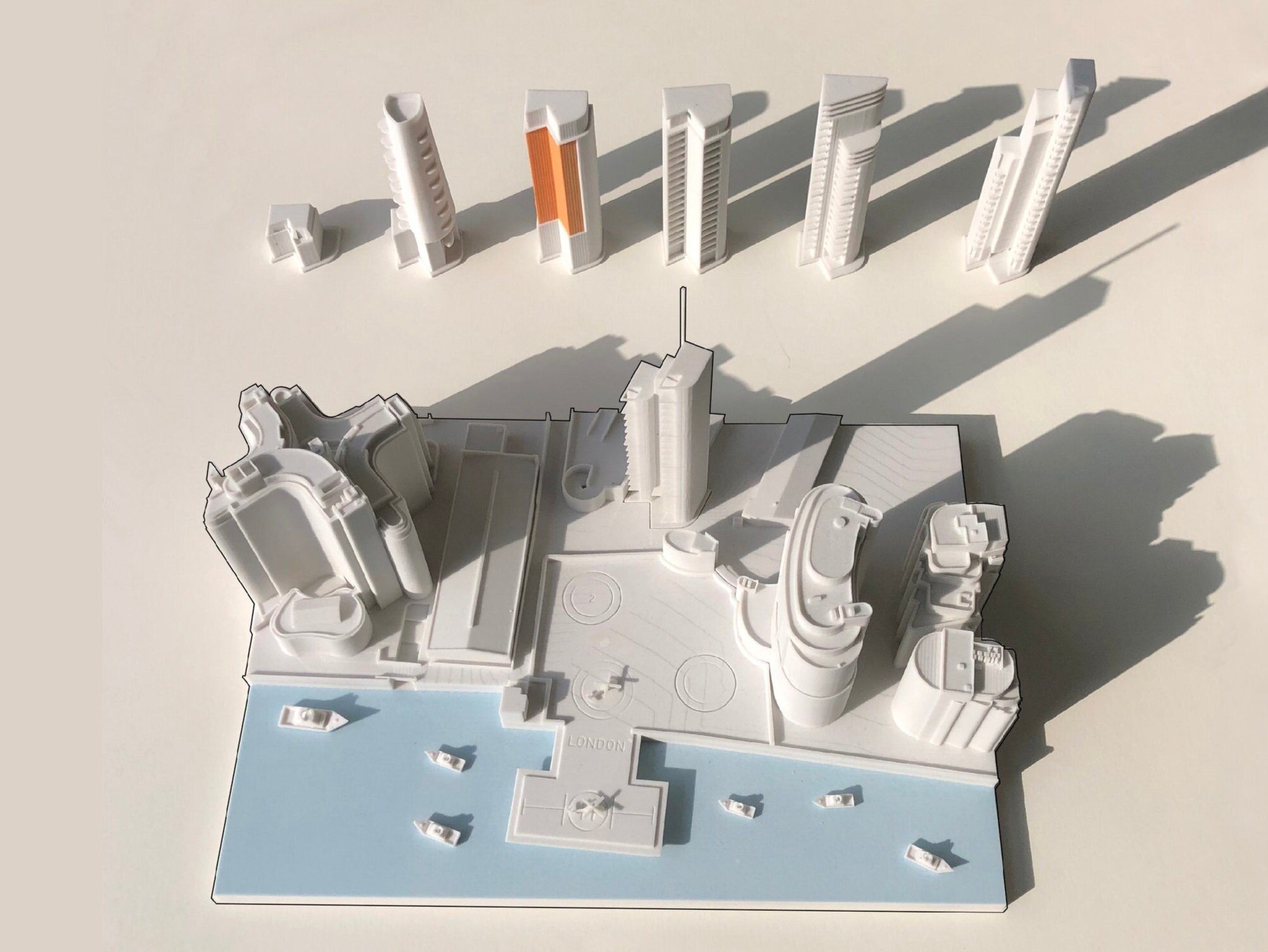

Fixie has slowly been working to debunk this myth and the former truth. The end product that navigates these criticisms is a hybrid model: one that is enabled by 3D printing and finished where required or desired, by hand and traditional methods. When combined with the improved working methods, 3D/BIM-3Dprint workflows these models offer consistency, detail, affordable complexity and hopefully a degree of surprise.

Early concept render of Maynooth University’s Student Union Complex by Scott Tallon Walker Architects.

Of course, you’d probably be more likely to believe us if you saw an example of this for yourself. The following case study focuses on Maynooth’s Student Union Building (MSU) a project by one of Ireland’s largest and most well-established design practices: Scott Tallon Walker Architects. The brief for the model will not seem that unusual to most - an affordable model that demonstrated some of the key finer details of the facade and the shared covered space.

Imported 3D information, cleaned up and prepared for printing.

An A3 model @1:100 was chosen as a scale and size that was both affordable and could reflect the necessary detail, whilst also being handy to carry to meetings and set in the centre of the board room table. A clean, monochrome white finish was also determined as the best route to ensure that the model focused on space and detail rather than attempting to represent materiality (which could have also added to time and cost).

The digital model for MSU was supplied initially from Revit (in an FBX format, so the first step is to remove additional detail that wasn’t necessary for 3D printing. Each 3D printing project is started by breaking down the model into manageable elements, working back from the finish desired. It’s important to know what 3D printing is capable of and to push the boundaries to ensure the most efficient use of resources for your client/end-user.

The focus of the model was the glazed pergola structure that connects the two buildings with a covered external space.

We knew that the perforated panels would not achieve anywhere close to the desired effect if 3D Printed at this scale (the holes being 0.1mm in diameter). It was therefore decided to have this detail brass etched.

The pergola, although delicate, was achievable through 3D printing. However, for the glazed canopy, we reverted to traditional methods again - laser cutting and etching clear acrylic to be placed onto the structure of the 3D printed part. By breaking down the model into its constituent parts it allowed all of these elements to be brought together after being 3D printed, post-processed and spray finished.

The result is an affordable model that achieves a high level of detail through the best combination of available methods and most importantly clearly communicates key design intentions.

Model Cost: £1,850 + VAT

Turn Around: 10 working days (including model assessment, file preparation, 3D printing, brass etching, spray finishing).

To see a version of this model being created in real-time watch our Fixie overview created for the AJ100 awards 2020.